I have a Swiss friend who is infamous for his unwavering pragmatism in the face of invitation. If someone asked him if he wanted to do something – grab a bite to eat or go swim in the creek – he’d almost always agree to join in, if he didn’t have other plans: “Why not?”

I was thinking of him when I agreed to a money-making opportunity on Thursday. It was my second day in Qufu, a city in China’s southwestern Shandong province. It’s known throughout China as the birthplace Confucius, and nothing else. It’s a poor and gritty city, where air pollution has stained the sky perpetually grey and residents drive shabby motorbikes and half-constructed tuk-tuks through dusty streets. It’s called a third-tier city, and without its connection to ancient Chinese history, it would be nothing more than a gray blot among gray blots.

The Confucius Temple in Qufu

From Beijing, it took me exactly two hours by high-speed train to get to Qufu. Until the outskirts of the city, where the landscape becomes dynamic and mountainous, the view from a train window is painfully predictable. Miles of flat farmland are interrupted briefly by drab, hastily constructed cities and condominium parks, although to call these “parks” is misleading when there is nothing green in sight.

The unnaturalness of the cities – I passed Tianjin and Dezhou – is unrelieved by farmland, which too has a feeling of artificiality, with its square plots of land and pencil-straight irrigation canals. Every plot of earth is utilized, hardly anything left to nature’s command. Wilderness is an unfulfilled promise here.

The peasants working the field, surprisingly few and far between, looked small against such a never-ending backdrop, like tiny figurines moved by an invisible puppeteer. They worked with the same tools used by their ancestors thousands of years ago, and the only difference between their landscape now and then were the motorbikes, radio towers, power lines and water-heaters. Everything else was the same.

I had come to Qufu to meet up with my friend Matty, an old friend from high school who spent the last nine months teaching English at Qufu Normal University. We were sipping coffee at the campus cafe when he got a WeChat message from a friend, who worked for a “training school” and wanted a laowai to help advertise the school that afternoon.

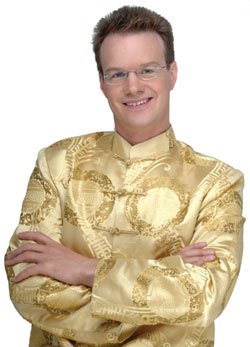

Canadian expat and famous “laowai” Dashan (Mark Rowswell), for many a polarizing entertainment figure in China

“Do you want to do it?” Matty asked me. “They’ll pay you 100 RMB.”

I thought about it for a second. “Why not?” I said.

Three hours later, I was in the back of a three-wheeled motor cart being driven by a boy named Smiley. Sitting with me were Kate and Abby, two college students at Qufu Xingtan University and employees at the Excellent A Training School.

We drove through the dusty boulevards of Qufu, past the ancient walled town in the center of the city and out into the surrounding countryside, where rows of corn, which the locals call “sticks”, dominated the earth. Kate and Abby chattered happily as our cart buzzed past piles of freshly pulled crop surrounded by dirt-stained farmers. They teased Smiley whenever he went too fast through a speed bump.

We arrived outside an elementary school. There was a couple old tables and stools stacked along a wall, and Smiley threw them silently in the back of his cart and drove a few yards to where adults were standing patiently by their battered motorbikes, waiting for the school to get out. A red banner along the school gate read: Delve deeply into developing “educational safety”.

Most of those waiting were grandparents, as the parents were farmers and would be working in the fields until mid-evening. We set out the tables and stools, and Kate and Abby pulled out a pile of flyers, a sign-up sheet, and pen. What occurred next happened in seconds: we were surrounded by chirping old peasants, eager to hear my new colleagues’ sales-pitch.

Kate and Abby handled them with ease, handing out flyers and explaining the benefits of the training school. Some of them listened intently, while others hung around, entertained by the commotion. Within minutes, Kate and Abby had six names and phone numbers on the sign-up sheet.

Ready for business!

The Excellent A Training School promised to improve students’ English grades; hence, the suspicious “A” in the school’s name. For a few hours a day, at 380 RMB (or US$60) for 30 days, the students would receive English lessons and lunch. The training school targets the farmers because many of them hadn’t received a good enough education to help their children with homework.

Training schools are highly popular in China, and the competition between them is high. Kate estimated that in Qufu alone, there are over two hundred. Training schools don’t all focus on English, either; there’s a training school for nearly every subject, from science and math to music and writing.

A Qufu resident whom I spoke to, a college student whose English name was Peter Philadelphia, works at another English training school during the summer. He was critical of them, believing they focused too much on boosting grades and not enough on improving students’ learning abilities. “I wanted to improve their learning, but they only wanted me to do their homework for them,” Peter lamented.

In the birthplace of Confucius, who taught unquestioning loyalty to ones’ superiors and stressed the importance of test taking, this seemed like a completely normal problem to have.

Kate’s school, of which she is the manager, was started three years ago by a 24-year-old graduate of Qufu Xingtan College. They currently employ three teachers. All of them are college students, as it is illegal to employ officially registered teachers at a training school. (They’re cheaper, anyway, Kate added.) For one month of teaching, they receive 2000 RMB, around US$300. One of the photos on the flyer was of a white man teaching a classroom of Chinese students and was captioned, “Our foreign teacher.” The other was of a crowd of children and read, “Watermelon competition.”

The gates opened, and a crowd of boys sprinted out like racehorses. Some of them ran over to our table to see what was going on, but most just hopped on the back of their grandparents’ motorbikes and sped off. The school was next to a busy road where motorbikes zipped alongside giant trucks carrying sand, gravel, wood, and other construction materials. When the kids rushed out of the school, the street erupted in the sound of car horns.

I pointed at the trucks: “Why are they honking?”

“So the kids know not to run into the street,” Kate answered, matter of fact.

By the end of the session, the Excellent A Training School had collected twelve names and phone numbers. Three of the new sign-ups made 100 RMB deposits to reserve a spot in the upcoming class period.

I hadn’t said more than five words. “Why did you bring me here?” I asked.

“So the parents will believe that the education is more official,” Kate said.

My white face had added legitimacy to their English teaching business: I was paid $15 to sit and smile.