Before traveling to Taiwan last year, I knew only a few things about my birth mother Susie (her American name). She was born in 1950 and grew up in Tainan in the southwest of Taiwan. In the 1970s, she immigrated to Las Vegas, and she worked briefly as a card dealer at a casino. While visiting Taipei in 1980, she met an engineer on a British ship; he would become my birth father. She gave birth to me in Las Vegas on April 9, 1981, and a few weeks later, she put me up for adoption.

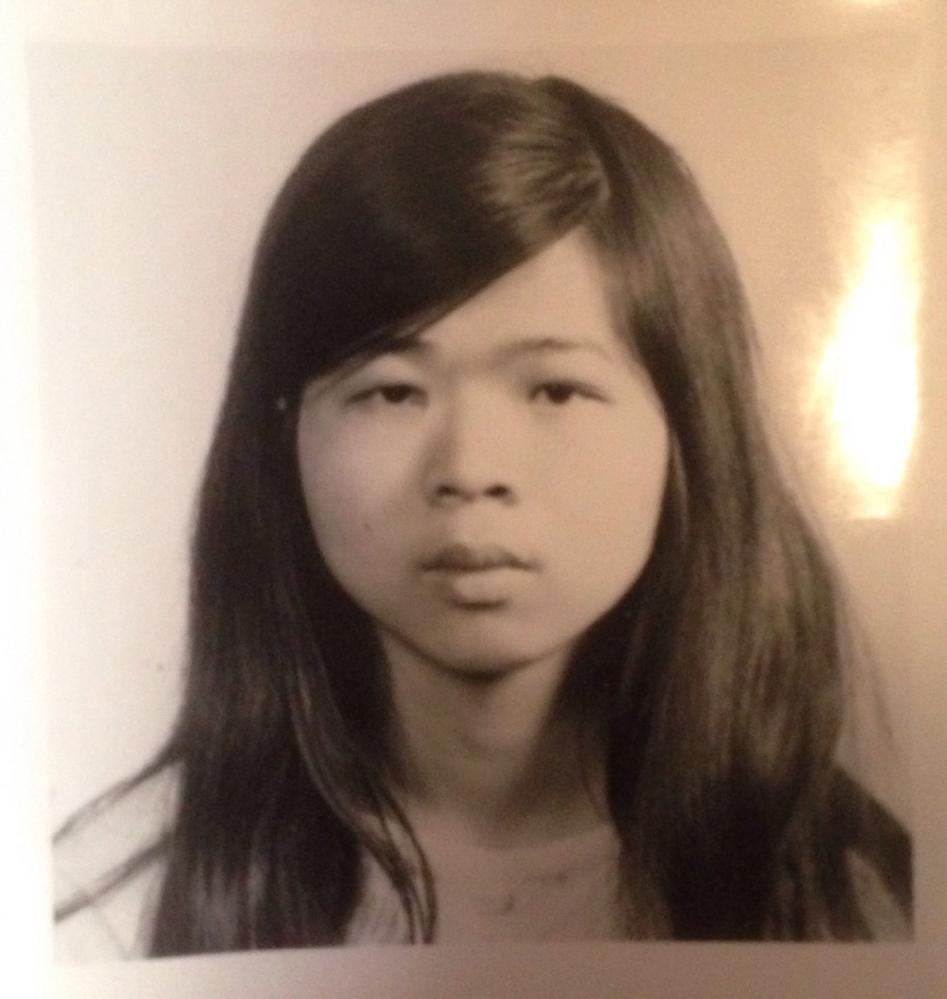

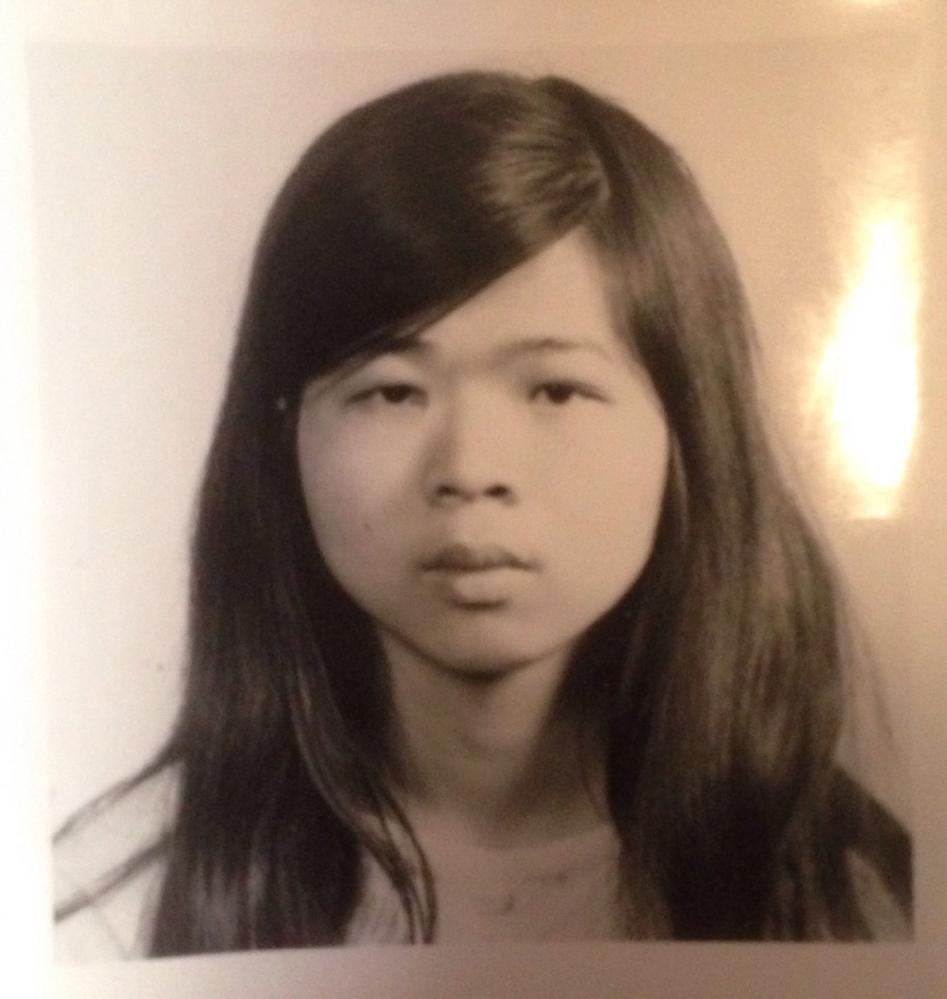

Susie’s passport photo in 1975, when she was 25

In September 2012, my start-up 1000memories was acquired by Ancestry.com, setting off a chain of events that would lead me to Taiwan to look for Susie. Suddenly, family history was my full-time job, and I felt inspired to learn more about my birth mother. I petitioned the Family Court of Clark County, Nevada, to open my adoption records. The Court granted my request, revealing Susie’s last name.

Susie’s last name led me to her younger brother and sister in Las Vegas, whom I found by cold calling numbers in an online telephone directory. A DNA test verified our relationship. Susie’s siblings had lost touch with her in the 1980s, and they guessed that she had moved back to Taiwan. Her brother gave me a passport photo of her when she was 25 years old, as well as an immigration document with her name written in Chinese, her birth date, and Taiwanese identification number.

When I left Las Vegas, boarding the first of three flights for Taiwan, I had many questions. Was Susie still alive, and if so, was she in Taiwan? What did she do? Did she have a family? Why had she lost touch with her siblings? How would she and I feel if we met? What would happen afterward? I imagined many different stories and scenarios - but not what was about to happen.

I arrived in Taipei at night on Wednesday, October 23. Within 24 hours, I hit a dead end. An official at the local government office in Taipei told me that Susie had left for the United States on March 25, 1981, two weeks before I was born. The Taiwanese government had no record of her ever returning.

I spent the next few days exploring Taipei, taking long runs to help recover from jet lag, and contemplating my next move. I called Susie’s siblings, but they didn’t know more than what they had already told me. I reached out to a few private investigators in Taiwan. They suggested I go on Taiwanese TV to tell my story (apparently, many Taiwanese-Americans have been reunited with lost family members this way). Disappointed, I wondered if it would be more fruitful for me to shift my search from Susie to my birth father Thomas Llewellyn Hughes—who, I suspect, remains in Asia if he’s still alive at 83.

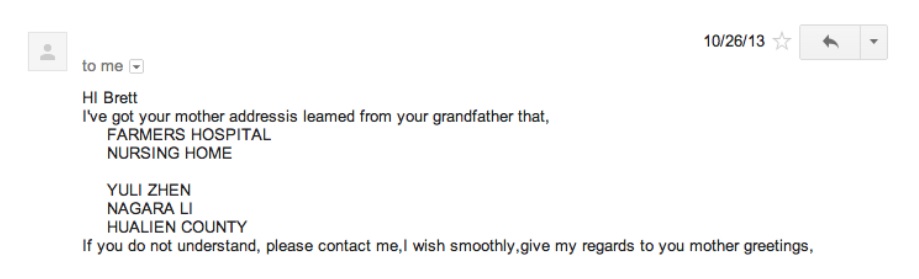

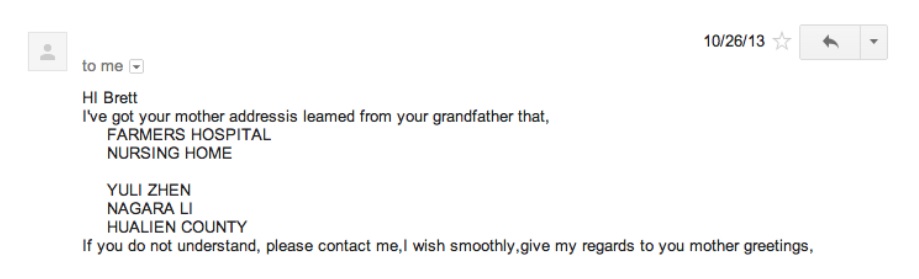

Then, on Sunday, I had a breakthrough. Susie’s oldest brother David called me. David also lives in Las Vegas, but we had not met because of an ongoing dispute between siblings. Despite barriers in communication (I do not speak Mandarin, and David has an accent and unique diction in English), I explained that I was in Taiwan looking for Susie. Within a couple hours, he emailed me an address in Hualien, a rural county on Taiwan’s remote eastern coast.

I asked for help from the Westin Taipei’s concierge, a young woman named Alice. Without offerings details, I gave Alice the address, and told her I was looking for a woman named Susie born on May 3, 1950. Alice googled the address, called the number she found, and spoke for a few minutes in Mandarin with the person who answered. After hanging up, she turned to me and said:

They say there is a woman there named Susie. She is approximately the same age as the woman you are looking for, but they cannot confirm her birth date because they do not know what her birth date is. Are you sure this is the right place? I do not think this is the place you are looking for. It is called Farmers Hospital. It is for the homeless.

The next morning, Alice and I met at Taipei Main Station at 7 a.m. Alice, who had graduated from the University of San Francisco a few years earlier, offered to accompany me as a translator on her day off. On the four-hour train ride, Alice and I talked about life in San Francisco, and she taught me how to count from 1 to 10 in Mandarin.

Mostly, I wondered if the Susie I would meet that day would be my birth mother — and, if so, what it would be like to meet her. We traveled down the mountainous eastern coast of Taiwan, between the sea and the green mountains, past the municipal capital Hualian, past the Taroko Gorge where most passengers got off, past the rivers and rice fields of southern Hualien County, until eventually we arrived in the sleepy farming village of Yuli. I felt a little bit like Marlow in an idyllic version of Heart of Darkness: nervous and excited in a foreign land.

We took a 15-minute taxi from the train station to the hospital outside of town. I left my suitcase with the security guard out front.

The women’s building at Farmers Hospital in Yuli

When we entered the women’s building of the hospital, Susie was standing in the middle of the TV room. There were perhaps 10 other women, whom the nurse quickly ushered out. All of them, including Susie, were wearing orange sweat suits. I noticed that Susie was short and chubby, and her black and white hair, cut short like a man’s, stuck up wildly in the back - like mine does when I have bedhead.

“Hi,” I said. She smiled but didn’t say anything. The nurse explained through Alice that Susie is nearly deaf, and she can only hear if you shout Mandarin into her left ear.

We sat down on the green plastic couch, and we tried to have a conversation. Shouting into a 63-year-old stranger’s left ear felt awkward, so Alice and I “spoke” to Susie by writing Chinese characters on white sheets of paper. Susie read them and then responded with short, simple answers.

Susie and I on the green plastic couch

I asked Susie how she was doing, and how long she had lived in the hospital. I asked her questions about her family, her children, and her past. Her memory was hazy, and she could only remember the vaguest of details. She didn’t know how long she had been there. Her father worked in the Air Force. She went to high school in Tainan. She had lived in Denver and Las Vegas a long time ago. She had two sons and also a daughter. She could not remember her daughter’s name.

Convinced by our physical resemblance and similarities in our stories, the nurse began to tell Susie that I was her son. Susie shook her head and waved her hand in disbelief. The nurse kept repeating in Susie’s left ear and pointing at me, “This is your son!” Susie could not and did not believe it.

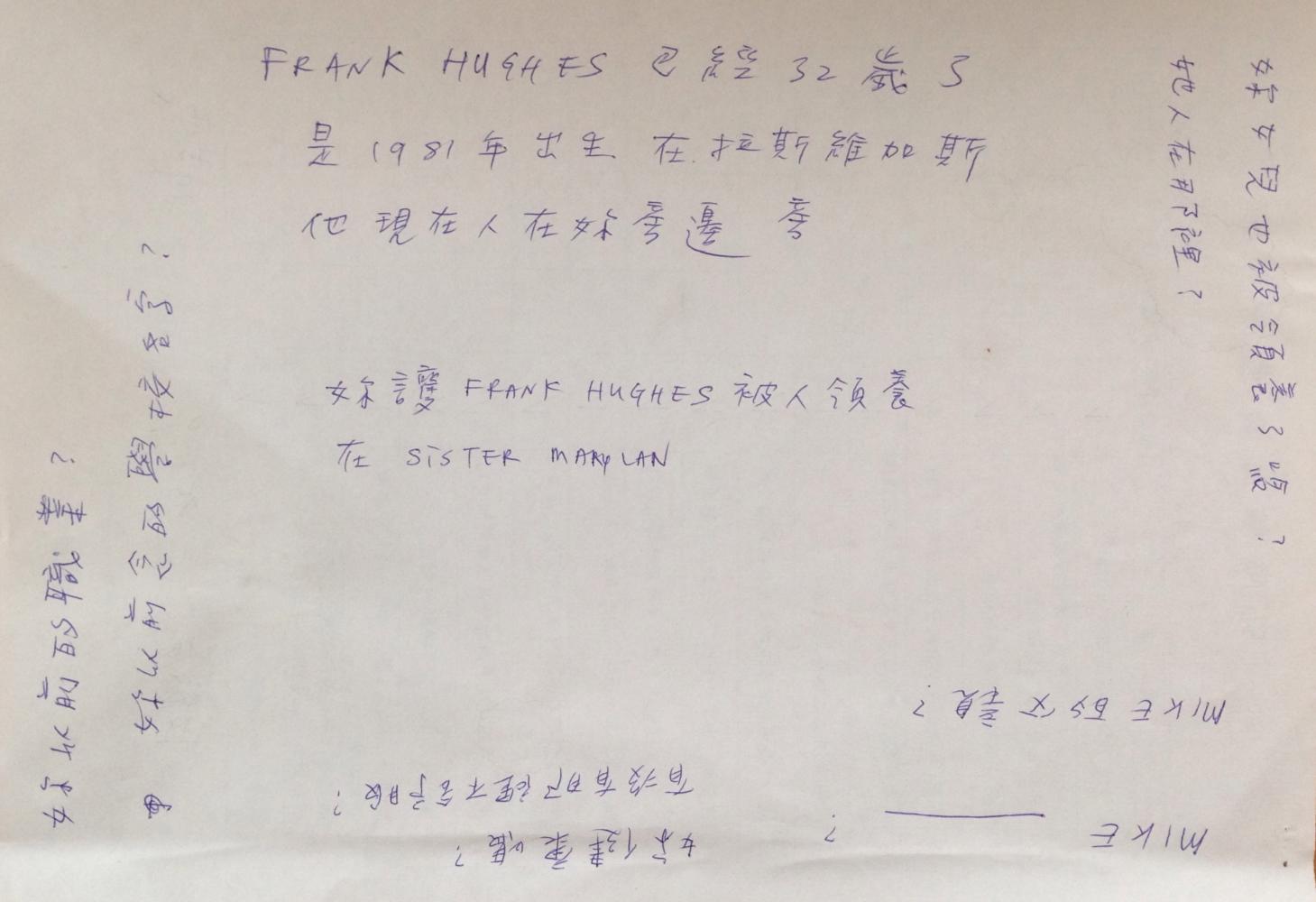

I wrote down on a sheet of paper in big capital letters, “FRANK HUGHES.” A few months earlier, I had learned from my original birth certificate that Frank Hughes was my original name. I showed the paper to Susie and pointed at the words.

One of the sheets of paper that Alice and I wrote on

“My son,” said Susie matter of factly. “Sì Jiǔ.”

Alice reminded me that Si Jiǔ means “four nine” in Mandarin. I realized that Susie called me Si Jiǔ to remember my birth date - April 9.

“I am Frank Hughes. I am Sì Jiǔ. I was born on April 9, 1981, in Las Vegas.”

Susie grinned widely, almost as if I had embarrassed her. She shook her head and waved her hand, and then she turned to the nurse and said: “My son would not visit from the United States. Plus, he is too handsome to be my son.”

The next day, I returned to the hospital to visit Susie and meet her social worker Sui-Ching. Mei, the warm-hearted, 60-year-old proprietor of my B&B, replaced Alice as my translator.

The social worker showed us Susie’s medical records. “Schizophrenia” jumped out in English — no translation required.

According to Sui-Ching, Susie was in good physical health but suffered from mental illness. Her symptoms had improved over the years, and her hallucinations had become less severe and less frequent. Unlike some of her roommates, she could feed herself and dress herself.

“How long has she been here?” I asked.

Sui-Ching explained that Susie was picked up off the street and admitted to a sister hospital in Taipei as an “unknown person” more than 16 years ago, sometime during the 1980s or 1990s. In 1997, the hospital in Taipei burned down, and Susie was transferred to Yuli. Unfortunately, nothing else about her was known because all medical records were destroyed in the fire, and her attending physician had passed away.

I spent the rest of the week in Yuli, visiting Susie once a day. I tried to think of activities that would make our communication deficiencies less apparent. Susie made it easy. She smiled a lot, and she seemed genuinely pleased that a friendly stranger had come to visit from the United States.

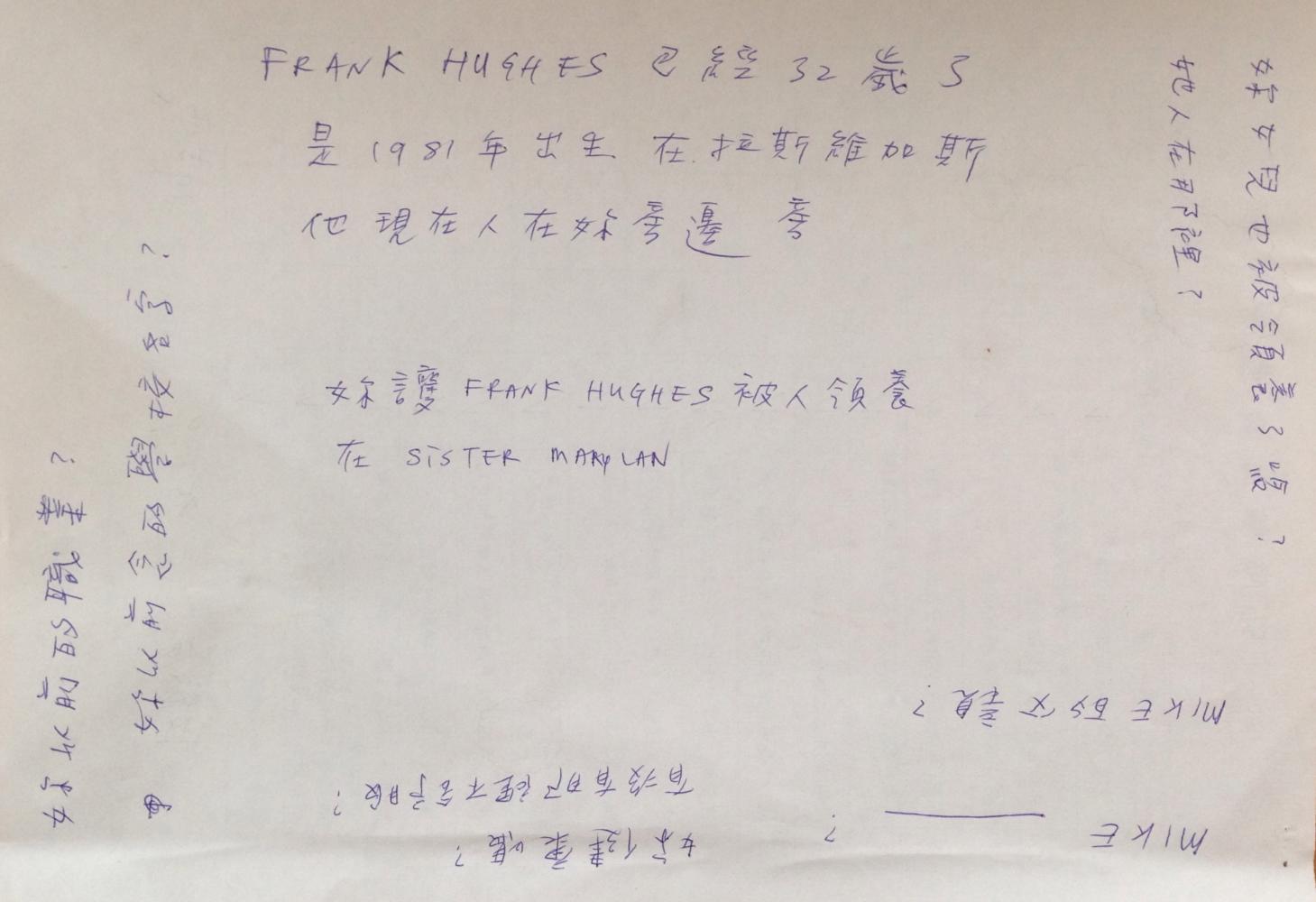

FaceTime with Mei, Sui-Ching, Susie, David, and me

We took walks around the peaceful grounds of the hospital. One day, her social worker and I took Susie to get her hearing checked at a clinic in Yuli. I wanted to buy her hearing aids, but Susie refused because they made the world too noisy. Another day, we used the internet connection at my B&B to make a FaceTime call to her older brother David. They hadn’t seen each other for 35 years. Susie didn’t recognize him at first, but after about 15 minutes, she understood who he was. She could not hear him, so she decided to write on a sheet of paper in Chinese, “I am happy,” and she showed it to him.

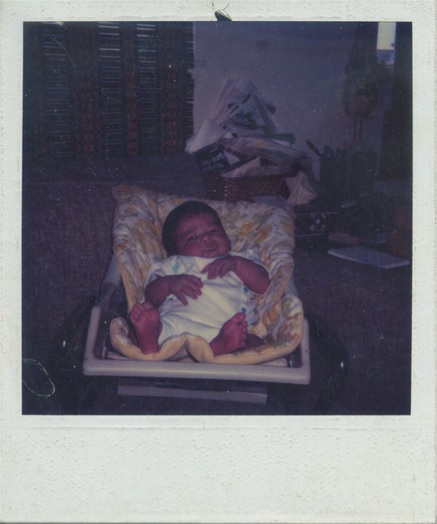

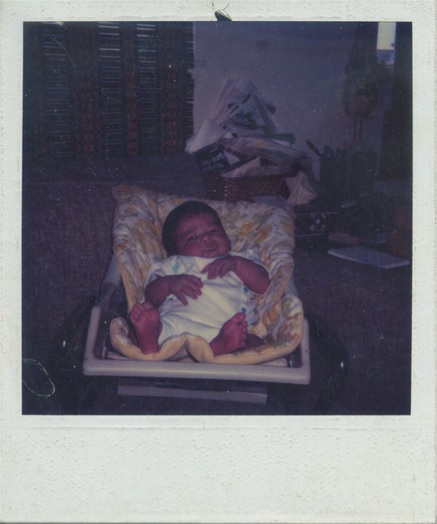

My first Polaroid

Each day, I showed her pictures on my MacBook Air of my evolution from baby, to boy, to adolescent, to adult, to the present day. I started with the first picture of me ever, a blurry Polaroid that Susie had taken herself when I was only a couple weeks old. I thought that through pictures, she might realize that I was her son. She never did.

At the end of the week, many questions remained unanswered. What triggered Susie’s schizophrenia and when? Did mental illness influence her decision to put me up for adoption? Why does the government have no record of her return to Taiwan? What happened to her in Taipei, and how did she end up on the street? Who and where are my half-brother and half-sister? Will I ever meet them or Thomas?

I wasn’t going to leave Yuli with these answers, but I did want to leave something behind for Susie. I wrote a short note, and Mei help me translate:

Your son Frank Hughes is very grateful to you for giving birth to him and for putting him up for adoption. He is now 32 years old and has had a very good life — loving family, great education, fulfilling career. He is happy and proud to be your son.

I also made copies of two photographs — the Polaroid of me as a baby, and a picture of us together from the visit. Sui-Ching laminated the letter and the photographs together so that Susie could keep them safe.

Maybe one day Susie will see the note and photos and realize who I am.

The author thanks Lauren Ladoceour, Beth Huneycutt, Ashley Huneycutt, Felicia Curcuru, and Rudy Adler for reading drafts of this memoir.

*

This article was originally published on Medium .