As the only child of an accountant working in a factory on the branch of the local railway bureau, I entered the Eleventh Railway Elementary School at the age of seven. Due to the fact that my school and my mother’s unit were subscribed under the same “system,” the fees was partially waived and the registration of my enrollment was relatively easy. (It’s no longer the case; a few years ago, the railway schools in my hometown were separated from the railway system by the enactment of a new policy.)

Neither exceptionally smart nor particularly docile as a kid, I was considered “annoying and unteachable” by my teachers in elementary school. On a daily basis, I was punished to stand up through the whole class for being “stupid”, “not paying attention”, or “talking to the neighbor.” Under my teachers’ intense glares and the mockery of my peers, I couldn’t focus on the lectures. My performance at school got worse; it increased the bad impressions my teachers had for me.

Who needs “tiger moms” when they’re waiting for you at schools?

Once, I forgot to bring my textbook to class; the angry teacher called my home immediately, reaching my grandmother and telling her (then a senior in her 60s) to come to my school right away. I remembered my grandmother hurrying into class within less than half an hour, tottering on her bad legs. She looked worried. I felt guilty, thinking of my parents’ warning to “not make trouble” for my aged grandmother, who helped to take care of me. In front of the class, my teacher told her that I was a “fool”, while I stood, looking down at my sneakers.

Another music teacher spent most of her time criticizing us – about our dirty hands, mindless attitudes, and so on. She seemed so frustrated at life that she needed to release her overwhelming anger… in the classroom. Each child was so terribly afraid of her. One girl even peed in her pants because she didn’t dare to ask for the restroom, crying in fear and shame when her wet clothing was discovered.

As I grew up, I learned to behave more attentively while interacting with my teachers so they wouldn’t find fault with me. There was only one exception when I was in third grade. The assigned homework was to review chapters in the textbook; I forgot to have my mother sign the book, which would prove that I’d completed the work; the absence would led to punishment. Realizing the situation, I tried to explain to the teacher.

Interrupting me, she shouted: “Don’t try to argue if you haven’t done the work!”

Unlike what I’d usually do, this time, I didn’t give up. The teacher grew impatient, and she picked a term from the book, ordering me to define it. I was nervous; of course, I failed to give the answer.

Roald Dahl’s Miss Trunchbull, unfortunately, existed outside of fiction

She was triumphant. “Ha! Is that how you reviewed at home? You were just looking over the terms before class, right? You think I don’t know? I’ve always kept a keen eye on you. You’re such a terrible liar.”

Hurt by this new charge, I reiterated my case. The teacher, vexed, frowned and made me leave the class and stand in the hallway until I admitted my dishonesty.

The vexed teacher frowned and ordered me to go out of the classroom and stand in the hallway before I choose to admit my dishonesty. The other students watched indignantly; they were used to, and probably tired, of the scenario – as well, the teacher was bound to win. For her, she wouldn’t make the situation easy for me: she had to make me confess, proving that she was always right, essential to sustain her authority.

Calling me back in ten minutes, she began her interrogation: “Admit it! You’re a liar!” Regardless of how much I protested, I surrendered in the end and burst into tears, believing that everyone in the class would look down on me. Now, I laugh at myself for being so naive: the teacher had dozens of these interactions with kids, and students barely recalled the episode before the week passed.

When I was young, I often looked forward to a cold or an illness so that I could avoid school. I think this may be a common feeling for children, but probably not so many would hope for these uncomfortable symptoms as desperately as me. Unfortunately, I was always a healthy child; under the keen eyes and care of my grandmother, I remained robust.

Years later, I learned from my mother’s colleagues that a few teachers who taught in my elementary school were workers in factories under the railway system. They definitely hadn’t attended colleges, and I’m not sure what level of education they had. In the factories, their employers could no longer bear their terrible performance at work, so they placed these workers on a special short-term training and sent them to schools to teach. Back then, these types of transfers weren’t difficult; the schools were short of staff, and most importantly, the schools and the factories were in the same “system” and under the same administration.

Of course, we have to question the validity of this information, but I don’t doubt the fact that many of my teachers were unqualified and downright unfit to teach children. Recently, some political reforms were launched in China, aiming to simplify the powerful and too-interconnected Chinese “systems,” though the results remain unclear.

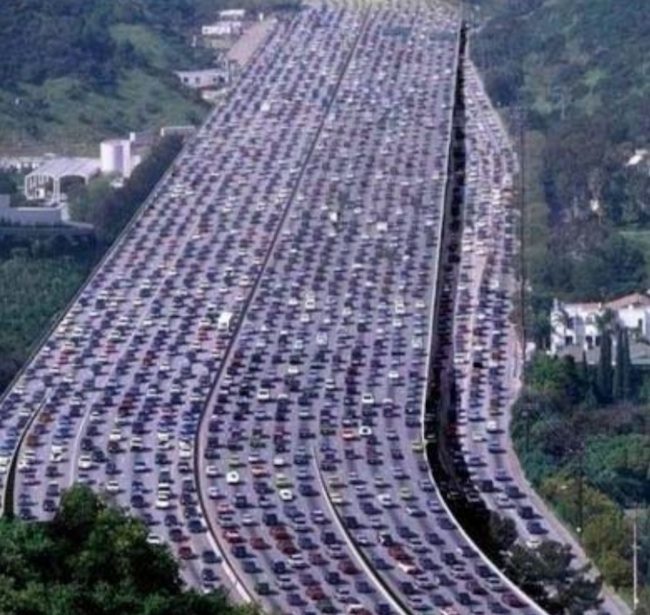

The quality of elementary education has improved since my time, partly enhanced by the competitive recruitment of elementary school teachers (from a pool of applicants with university and even Master degrees), as well as the growing awareness of parents in selecting a good elementary education for their children. Some parents buy apartments or homes in the neighborhood of the good public elementary schools because, according to policy, their children will automatically be assigned to these schools; others choose to pay and send their children to private schools. The trade-offs, though, are much higher costs in education, which has put much pressure on today’s parents, as well as increased stress and allegations of corruption.

I don’t have the answers to education policy, but hopefully, the younger generation in China would have a healthier experience in their lower schools than I did.

For another personal narrative of growing up under China’s railways system, check out Lusha Chen’s “The ‘Railway Kids’: Growing Up Under China’s Ministry of Railways.”