“Tragedy of the commons”, primarily an economic term that describes the phenomena of overused common resources, has become the drama in the everyday life of Chinese people. Public facilities like parks, libraries, and transportation, poorly maintained and regulated, are excessively exploited. Here are some typical scenes in China:

“Rush hour” at bus stations and subways

For many Chinese people living in big cities, fighting for seats – or even a space for one’s body – is a routine part of their life

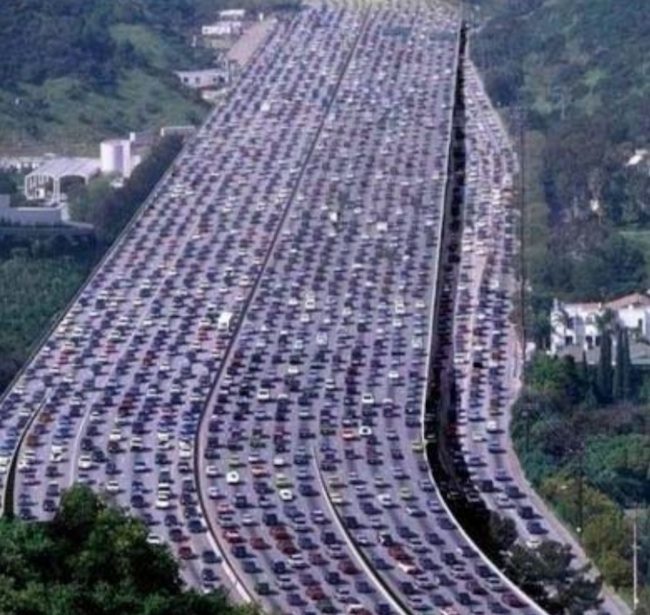

A traffic jam to rival the notorious Los Angeles lanes

The activity you see in the picture is called 广场舞, or “dance in the square”, which literally means a bunch of people dancing in a public square. “Though not artistically designed, this activity is quite popular among middle-aged women in China: indeed, such exercise is good for their health, though it’s definitely not the only option for exercising. However, these dancers take up a large public area, and the music they play is always loud and noisy.

In my hometown, I could barely walk in a nearby park without stepping on someone’s feet after the nightfall, because there were sometimes over four hundred people moving around in a space no more than 1,000 square meters (10,784 sq ft, or about the size of a baseball diamond). Due to the music and other noise, I needed to shout to my friend in order for her to hear me.

In my city’s public library, there was a study room. In China, from June to August is the period when many college students and graduates study for the civil service examination (a test used to select government officials) and the postgraduate entrance exam (think of it like the Chinese GRE). Yet, most of their dorm rooms or apartments are unbearably hot at this time of the year. As a result, the air-conditioned study room becomes highly desirable.

Last year, I witnessed the Rumble in the Library: by 8:00 o’clock in the morning, a large group had already thronged outside the gates of the library. A few guards stood inside the gates, keeping a keen eye on these people. Once the gates opened at 8:30 a.m., the group, some men in suits and some women in high heels, wrestling about and pushing aside their neighbors, stormed upstairs to the study room. I was dumbstruck by their valor and energy.

At the door of the room, there was a second line of security. A guard dragged a desk to block the door and let in only a limited number of people. Arms akimbo, he yelled to those of us who swarmed outside the door: “You, don’t push! If I ever see anyone sneaking in, I will kick that person out of the room!”

Inevitably, a large portion of those who successfully got in were young men, because they were physically advantageous. Once they’d secured a seat, these men sat down with a relieved sigh, fanning themselves with their papers and books. Not hurrying to their original purpose, they took their time, and with amusement, instead studied the crowd outside, as if they themselves hadn’t been one of the anxious, pushy mass a minute ago.

Other reading rooms in the library wouldn’t let people in to study. Each room had a staff standing at the door, checking the readers’ personal belongings: they weren’t allowed to bring in any of their own books, and they could only read newspapers or books offered in the room. In the end, I had to sit on the stairs and read my own book. It was even cooler on the stairs, though, compared to the air-conditioned rooms pack with bodies.

Excepting the problem of “moral rust” that exacerbates in the competition of common resources, I can see from my personal experience that this chaos also invited bullying by the library staff. Despite the intentions of the controversial “one child” policy, China’s population remains a large number. The amount of public facilities, on the contrary, is far from enough. Both factors compound the competition of common resources in China: the ideas of rule and morality evaporate in the face of scarce public resources and overwhelming needs.

No comments:

Post a Comment