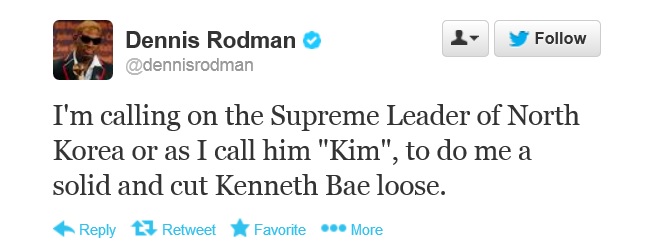

When Dennis Rodman, the former NBA rebound champ, tweeted, on May 7th, 2013:

His upcoming visit to North Korea in August 2013 seemed positive. Bae is an American missionary arrested in late 2012 in North Korea and sentenced to 15 years in early 2013 for crimes against the state. Loaded with confidence, Rodman even criticized President Obama and added, “Obama can’t do s**t, I don’t know why he [Obama] won’t go talk to him [Kim].”

“The Worm” called his upcoming visit in August a “basketball diplomacy tour,” suggesting that his method is in full effect and will revolutionize diplomatic relationship with international “loose cannon,” the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

However, Rodman’s comments – followed by his visit, not in August, but instead in September – precipitated doubts about his basketball diplomacy. Rodman’s response to the reporters in Beijing before crossing over to the North perplexed those who had hoped for a different answer. When asked about discussing Bae’s release with Kim Jong-un, Rodman commented, “I’m not going to talk about that,” and added, “Guess what? That’s not my job to ask about Kenneth Bae. Ask Obama about that. Ask Hillary Clinton.” These comments seemed to uncover Rodman’s guise of a “diplomatic” attitude.

Some still remained hopeful, however. Reverend Jesse Jackson Sr., a civil rights and religious activist, tweeted, “Congrads [sic] @dennisrodman on your diplomacy efforts in North Korea. It might be dark but you are a light!” This was deleted and replaced by, “… ping pong diplomacy worked in China, and Basketball seems to work in North Korea. #KeepHopeAlive”, referring to the method used in the early 1970s by Nixon’s administration to open up and build ties with the People’s Republic of China.

Kudos to Reverend Jackson for digging out a similar negotiation strategy from the past, but there’s a “minor” error in his comparison of the two: when Tim Boggan, the American ping-pong champ, and the rest of the team visited the PRC, they represented the United State of America and cooperated with the U.S. government to advance U.S.-PRC relations.

Unlike Boggan, when Dennis Rodman visited North Korea again on January 9, 2014, he’d become “BFFs” (best friends forever), with the young North Korean leader, the friendship struck when the two sat next to each other watching a basketball exhibition in Pyongyang in February 2013.

But when asked, Rodman had no interest of resolving Bae’s internment. Even worse, he sided with the North and brashly asked the press if they knew what Bae had done, implying that maybe Bae deserved his sentence. In turn, the U.S. responded to his actions by stating that Rodman was not a representative; Bill Richardson, a former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations who visited North Korea, followed up with this criticism and said Rodman’s comments “crossed the line.”

Rodman’s comments confirmed that as far as opinions on Bae’s captivity or Kim Jong-un go, he and the U.S. aren’t on the same page. He defended his visit: it was about opening “the door a little bit”, and indeed, taking the steps gradually may be the key. However, this January’s trip was his fourth to North Korea, and every time, he seems to be buddying up to Kim at the expense of becoming an enemy of the States. He’s no longer working towards “basketball diplomacy”, but rather, too busy entertaining Kim for the leader’s birthday.

Despite what many had hoped for, it appears that a leopard can’t change his spots. Rodman failed his own self-appointed diplomatic mission, his nation, and those who truly work for democracy and transparency.